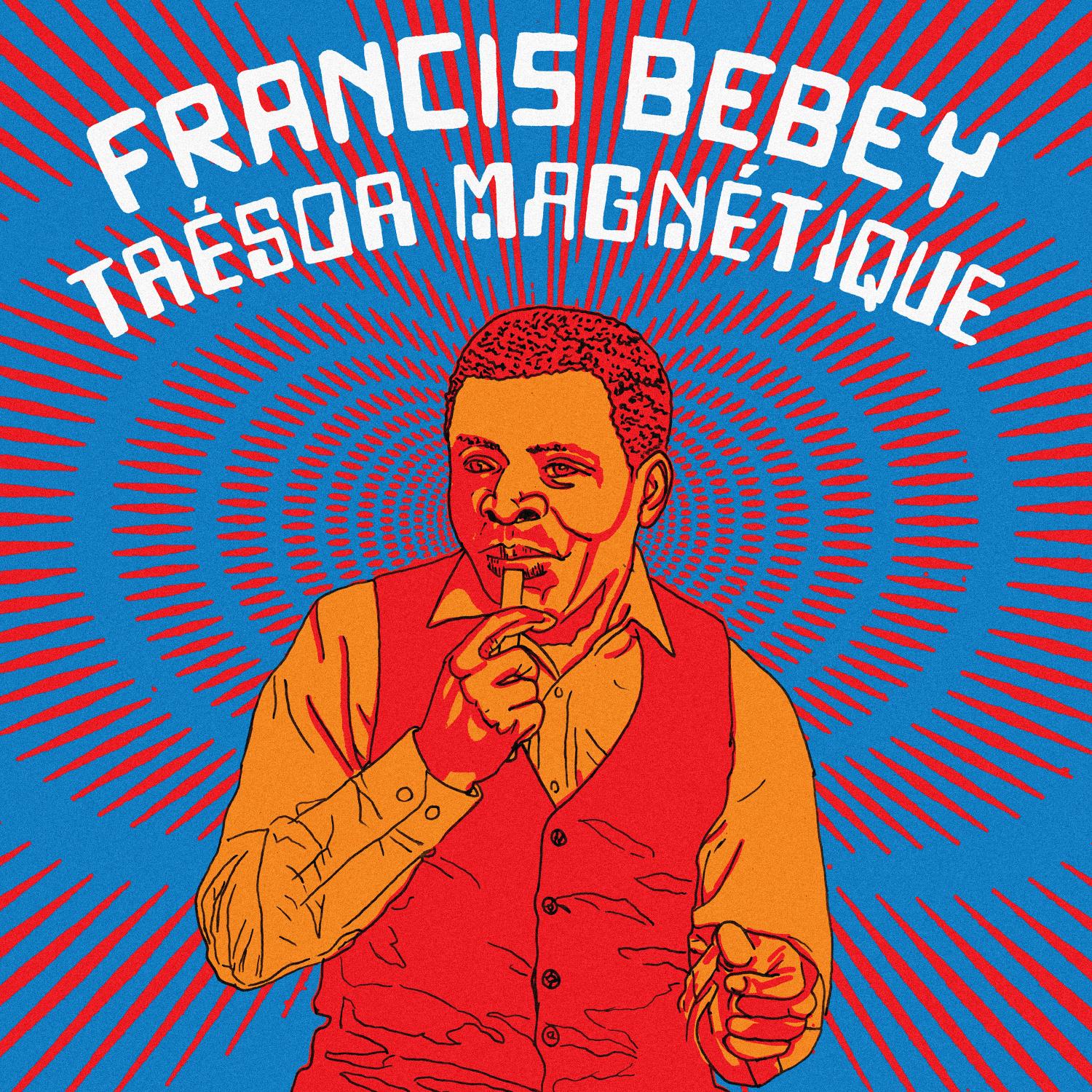

Francis Bebey

"Trésor Magnétique"

Africa Seven reveals a treasure trove compilation album of the late Cameroonian pioneer - Francis Bebey

Francis Bebey is the kind of artist whose legacy feels infinite.

To listen to his music is to be pulled into a vast and intricate web of ideas-each one carefully considered, fiercely independent, and inextricably tied to a sense of time and place, even as it pushes far beyond them. For Bebey, music was not just an art form but a philosophy, a way of asserting the richness and vitality of African culture on a global stage. He was both a traditionalist and a futurist, a man deeply rooted in the rhythms and melodies of Cameroon who also saw no contradiction in layering those sounds with synthesizers, tape loops, and drum machines. Bebey did not follow trends; he set them, often without anyone realizing until decades later.

There's a timelessness in his work-an open invitation to step into a musical realm where tradition and futurism walk hand in hand. To listen to him is to be pulled into a vast, intricate web of ideas, each strand precisely placed and fiercely independent, yet woven so tightly into a sense of time and place that you can almost smell the Cameroonian air. Even so, Bebey's music takes flight far beyond the borders of Cameroon and any era's notion of what "African" or "global" music should be.

His vision was never just about conjuring pretty sounds and catchy melodies; it was always grander than that. Bebey saw music as a worldview, a philosophy, and most importantly, a vessel for communicating the richness of African culture on the global stage. He was both the keeper of ancient rhythms and a daring innovator who found no contradiction in layering those rhythms with the synthetic hum of drum machines, or the eerie loops of tapes and early samplers. Long before "afrofuturism" became a buzzword, Bebey was pioneering his own version of it-asserting that African music could be everything, everywhere, all at once, provided it had a steady hand and a fierce intention behind the controls. He never followed trends; he created them, often so quietly that only decades later did people realize how seismic his influence had been.

Born in Douala, Cameroon, in 1929, Bebey grew up in a home bursting with books, music, and conversation, thanks largely to his father, a Protestant minister with a deep intellectual bent. In that lively household, religion and reason danced side by side: Sunday services mingled with philosophical debates, while local musicians serenaded neighbors from dusty courtyards. Young Francis soaked it all up. By the time he landed in Paris in the mid-1950s, enrolling at the Sorbonne to study music, he was armed not just with technical skills but also with a worldview forged by the interplay of homegrown rhythms and global ideas. Even then, he was already dreaming up a future in which African music wouldn't merely survive Western cultural waves but evolve in dialogue with them-and ultimately reshape them.

It was a radical stance, this belief that Western tools like synthesizers, drum machines, and tape loops weren't existential threats but rather potential allies. Many African artists felt pressured to pick a lane: either fully embrace Western pop idioms to "make it" abroad or cling to a narrower, idealized version of "traditional" African music. Bebey refused to let outside forces paint him into a corner. For him, the mixing board and the pygmy flute both had a place at the table, so long as they advanced the conversation about what African music could become. It wasn't about following a market's whims; it was about insisting African music belonged on every stage imaginable-by its own authority.

The implications of that philosophy have never been clearer than in the present, where African electronic music-whether it's Amapiano, Gqom, Afro-House, 3step, or yet-to-be-named hybrids-dominates clubs and streaming platforms around the world. Their deep basslines, polyrhythms, and digital textures trace a lineage back to artists like Bebey, who dared to ask what lay beyond the boundaries others assumed were fixed. Indeed, much of what we celebrate as today's African electronic renaissance could be read as the flowering of seeds that Bebey planted decades ago. It's no exaggeration to say that his forward-thinking approach carried the DNA for these future genres long before the global music industry caught on.

Tresor Magnetique, this compilation of unreleased tracks, archival recordings, and neglected gems from Bebey's vault, feels like a grand reveal in an ongoing narrative-a story that spans continents and generations. The compilation's name (translated as "Magnetic Treasure") sets the stage perfectly. Not only does it reference the fragile tapes discovered in the home of Bebey's son, Patrick, but it also hints at the almost gravitational pull of Bebey's art. Meticulously digitized at Abbey Road Studios, these tracks radiate clarity and urgency that defy the decades separating them from contemporary ears. One listen to Tresor Magnetique, and it's as if you're opening a letter from another era, only to find that its contents speak to you more vividly than today's headlines.

What makes Bebey's work stand out, even among the pantheon of African giants like Fela Kuti or Miriam Makeba, is his insistence on creative independence. While some African artists of his time pursued long-term contracts with global labels-looking for distribution, prestige, or simply the means to reach wider audiences-Bebey stuck to his own imprint, Ozileka. He did so at the cost of mainstream visibility, certain financial benefits, and even the risk of occasional obscurity.

Looking back, we see the wisdom in that choice: he preserved his freedom to experiment without external gatekeepers telling him what to play or how to sound. It's a rare feat in any age, let alone in an industry that frequently sought to pigeonhole African music into safe, predictable compartments. One might be tempted to frame Bebey as prophetic-the man who foresaw a future of global African beats pumping through speakers in Berlin, New York, or Tokyo. Yet casting him as a prophet risks oversimplifying his creative complexity. Bebey was less about gazing into a crystal ball and more about kindling possibilities. He deeply believed that African music could shape global culture, and he devoted his life to proving it-in his recordings, his writing, and his tireless advocacy for artists who might otherwise have been overlooked. His music demands active, inquisitive listening; it wasn't crafted to please passersby but to engage those ready to embrace its layers.

The scope of Bebey's artistry extends beyond the music alone. His lyrics brim with social commentary, delivered with a nimble combination of humor and earnestness. "La Condition Masculine" (English Extended Version) pokes at patriarchal norms, dancing right in that sweet spot between levity and razor-sharp critique. "Dash, Baksheesh & Matabish" skewers corruption with an equally playful vibe-casting bribes and clandestine deals as a universal oddity rather than a localized sin. The net effect is that you can't help but sway to the beat, even as you recognize the incisive jab at universal failings. On the more intimate side, "Immigration Amoureuse" paints a picture of a love constrained by borders and bureaucracies. For many Africans who journeyed or migrated to Europe, Bebey's depiction rings painfully true. Another track, "Where Are You? I Love You," tugs directly at the heart, a raw confession of longing that transcends linguistic and cultural frontiers. In these songs, Bebey's gift for uniting the personal and the political becomes crystal clear, urging listeners to understand that romantic struggle often has real-world, systemic underpinnings.

Yet if you dive deeply into his repertoire, what stands out most is his restless drive to experiment.

In an era when African artists were sometimes stuffed into marketing categories like "world music" or "folk," Bebey adamantly mixed and matched instrumentation that had seemingly no business coexisting. A pygmy flute might flutter against the metronomic pulse of a drum machine, or a classic guitar riff might coil around a looped synthetic soundscape. "Forest Nativity (Extended Version)" exemplifies this collision of tradition and modernity, weaving thumb-piano motifs with ghostly electronics. In hearing these recordings, you get the sense of a mind in constant motion, rarely content to finalize a piece and move on.

Alternate versions like "Je Vous Aime Zaime Zaime (Alternate Drum Machine Version)" reveal subtle, sometimes seismic, transformations that occur when a live rhythm section is replaced with mechanical pulses. "Agatha (Alternate Version)" and "Savannah Georgia (Alternative Version)" likewise demonstrate his compositional curiosity-tweaking a chord progression, adjusting a drumline, or layering a different vocal take. The net result is an insider's glimpse at how Bebey's creative process was shaped by never-ending experimentation rather than singular flashes of inspiration.

What Bebey was doing was not about prediction-it was about possibility. He believed that African music had the power to shape the world, and he spent his life proving it, whether through his own recordings, his writing, or his tireless promotion of artists and ideas that others might have ignored. His music was not made for the masses; it was made for those who were willing to listen closely, to engage with it on its own terms. This compilation takes us deeper into that world.

Any tribute to Bebey must also acknowledge the bigger tapestry of African music in the 20th century. The century was marked by political upheavals, decolonization movements, the birth of new nations, and the forging of new cultural identities.

Musicians grappled with representing these emerging realities, deciding whether to look inward for purely local sounds or outward to form global connections. Bebey did both simultaneously, forging a path that insisted African music not only belonged on the world stage but had every right to steer the conversation. That approach extended to his journalism and cultural ambassador roles. Bebey wrote essays and novels that probed the complexities of postcolonial Africa-its redefinitions of identity, its emergent voices, and its negotiation with global paradigms. He spent time at UNESCO, actively championing the preservation of traditional African music, but always with an eye toward how these traditions could spark new forms of creativity. In his worldview, there was no tension between cherishing what was old and venturing into the unknown. Both impulses fueled the same engine of progress.

That's why Tresor Magnetique feels less like a dusty retrospective and more like a living, breathing dialogue with the present. For newcomers, it offers a doorway into a vast discography that moves fluidly between danceable afro-funk, folkloric chanting, politically charged commentary, and shimmering electronic explorations. For longtime fans, it unearths new corners of a beloved catalog, revealing how Bebey's restless spirit never quite let a song rest in one configuration for too long.

In many ways, Bebey's life story encapsulates the arc of African intellectuals in the 20th century: from a colonial environment to a Europe that sought to define them on its own terms, to a courageous forging of self-definition and a reshaping of global culture from the inside out. When he passed away in 2001, literally mid-performance, it was both a heartbreaking collapse and a cosmic statement: he died doing what he loved most, serving the music until his final breath.

Tresor Magnetique stands as a timely-and timeless-reminder of this continuity. It articulates the unshakable pull of Bebey's artistry and the sheer value of these recordings. In a modern age swarmed by fleeting digital trends, Bebey's work stands like an anchor that refuses to let us drift too far from the core truths of creativity. It urges us to seek depth over superficiality, vision over trendiness, and genuine cross-cultural dialogue over comfortable echo chambers. For the uninitiated, the compilation is an exquisite entry point. It beckons you to keep digging-to seek out older albums, read his essays, maybe even explore the broader Cameroonian music scene from which he drew inspiration. For those who have cherished Bebey for years, it's a chance to revisit him anew, to be reminded that even the recordings you thought you knew might still hold hidden angles and unexplored crevices of sound.

Francis Bebey wasn't merely "ahead of his time"-he operated on his own timeline entirely. In a century that often demanded conformity or neat categorization, he insisted on an expansiveness that belongs just as much to the future as it did to the mid-1900s. And that is why, as we immerse ourselves in Tresor Magnetique, it feels like we're not just discovering lost artifacts-we're confronting ideas that remain radical and relevant right now.

Francis Bebey was not just ahead of his time-he made his own time. And now, we finally have the chance to catch up.

UNCUT, July 2025 - “Rescued from decaying tapes by his son and digitised at Abbey Road, Trésor Magnétique compiles 20 unreleased tracks, alternate versions and overlooked gems on which bamboo flutes and thumb pianos are looped and layered with deep bass grooves and synths to create a polyrhythmic trad/futurist fusion that signposts the way to almost every trend in current African electronic dance music.”

All songs written and composed by Francis Bebey

Vocals, Guitar, Kalimba, Percussion, Flute - Francis Bebey (tracks A1-D5)

keyboards, flute, drums – Patrick bebey (Track A2) Keyboards [Basse Clavier] (tracks B2,B3)

Bass Guitar - Jean-Claude Ebongue (tracks: A4,C2,C4,D1,D2,D3)

Drums & Percussion - Brice Wouassi (tracks: A4,C2,C4,D1,D2,D3)

Keyboards - Dominique Luro (tracks: A4,C2,C4,D1,D2,D3)

Published by Dharma Songs

Project curation by Romek Boyer and Nahida Tarbaoui

Label Executive John Bryan

Sleeve notes by Dare Balogun

Artwork by Pau Pahana

(P) and (C) Africa Seven 2025.

Under license from Ozileka

www.africaseven.com

www.ozileka.com

| 1. | Forest Nativity (Extended Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 2. | Le Grand Soleil De Dieu | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 3. | La Condition Masculine (English Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 4. | Quand Le Soleil Est La (Alternate Drum Machine Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 5. | Ganvie | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 6. | Kikadi Gromo | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 7. | Immigration Amoureuse | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 8. | Where Are You I Love You | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 9. | Dash, Baksheesh & Matabish | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 10. | Je Vous Aime Zaime Zaime (Drum Machine Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 11. | Agatha (Alternate Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 12. | L' Amour Malade Petit Francais | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 13. | Ndolo | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 14. | Chant D'Amour Pygmee | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 15. | Funky Maringa | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 16. | Crocodile - Crocodile - Crocodile | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 17. | L'Ile De Djerba | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 18. | Kitibanga | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 19. | Asma (Alternative Instrumental Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

| 20. | Savannah Georgia (Alternative Version) | Buy Track ( 0.69) | ||

|

Buy All Tracks ( 9.66)

Buy Physical 2xLP (22.02) |